Male mountaineers should be more mindful of womenâs concerns about their personal safety in remote areas and avoid patronising them by questioning their map-reading abilities, a climbing expert has said.

The advice comes in response to female hillwalkers and mountaineers saying sceptical attitudes towards their skills and unwanted attention are discouraging women from taking up the sport.

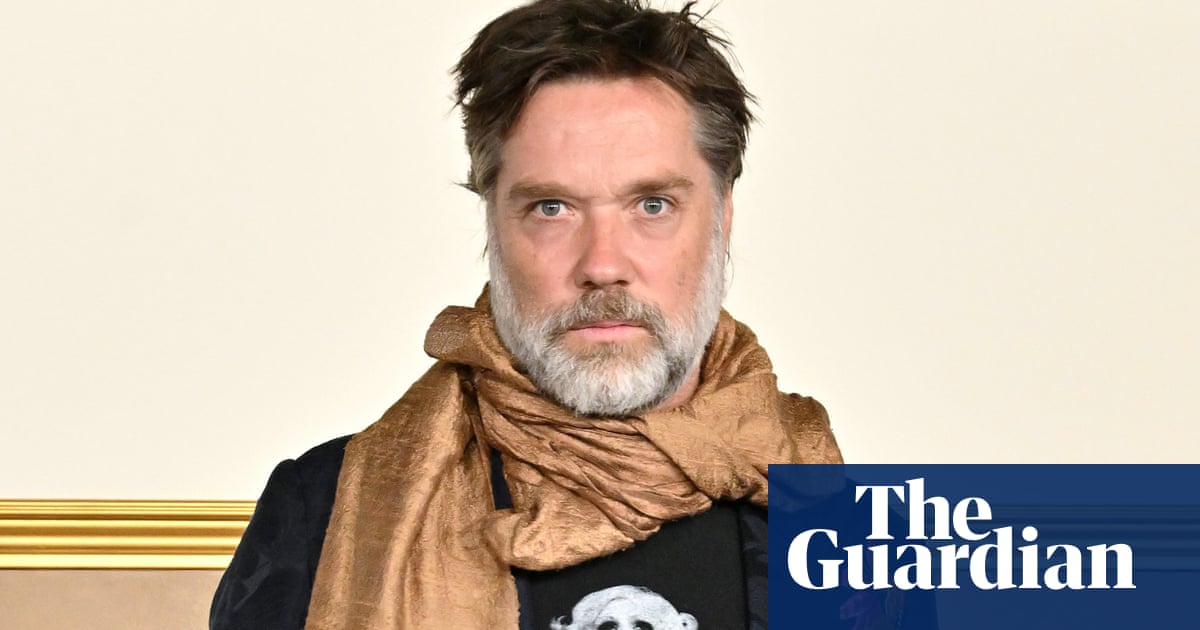

Writing in the latest edition of Scottish Mountaineering, Richard Tiplady, a Scottish Mountaineering member, made several recommendations based on âhorror storiesâ from women.

These include that men abstain from asking women about their route, do not push invitations to walk together or pitch tents in close proximity, and avoid giving condescending or unsolicited advice or greeting them with dated language such as âdarlingâ or âsweetheartâ.

He added: âNever ever say to a woman: âIâll walk with you to keep you safeâ (this rings major alarm bells).â

Tiplady wrote: âItâs rather simple. Respect peopleâs boundaries. Be friendly but donât try to be friends. Treat someone as they would like to be treated. Then clear off and leave them alone.â

Tiplady said he was motivated to write the advice after learning from female friends that âmen donât realise how much women feel patronised by men on the hillsâ.

âThis is just life, itâs not just the hills â but the hills are not necessarily different to anywhere else,â he said, adding that he had learned âIâve got to handle myself in a way that makes [women] feel safe and secure, but in a way that doesnât make [them] feel patronised.â

Keri Wallace, a mountain leader in the Scottish highlands who co-founded Girls On Hills eight years ago to encourage more women to enter the sport, said she saw the advice as âan extension of the womenâs personal safety issue we already see in the streets,â particularly in relation to being catcalled or harassed while running.

She previously surveyed female walkers about barriers and found over 50% had concerns, including around going to the toilet outdoors and venturing out in all-male groups.

She feels that there is a lingering effect on womenâs confidence and sense of belonging from historical attitudes that âfrowned uponâ women going out in the mountains, believing them to be too delicate and weak.

These remained as âperceived or soft barriers, almost as a byproduct of the culture we still have around womenâs abilities relative to menâ.

In Wallaceâs own excursions, she is regularly questioned by men about whether she knows how far away the summit is, prompting comments such as âsurely youâre not going the whole wayâ, as well as expressions of surprise that she is a mountain leader, which she said could make you âfeel like you donât really belong there or youâre not competentâ.

Wallace said these issues were primarily about confidence rather than safety, since assaults in the mountains are virtually unheard of. But she acknowledged that women carried over valid safety concerns from cities into wild areas, discouraging them from wild camping or staying in Scotlandâs remote unlocked refuges, bothies.

She said men being mindful of this and giving women space when they encountered them alone could help women feel more comfortable, as it showed a level of consideration.

Ian Sherrington, the head of training at Glenmore Lodge who takes part in the Mountain Safety Group network, said he was not aware of formal discussions around womenâs comfort and safety but he felt this was âvery worthy of further investigationâ.

âI would dig deeper first â [it] could be by approaching groups represented that have a concern,â he said. âI believe trained and qualified mountain leaders already played a positive part in supporting individual confidence in the mountains. Further learning in the best way to do that is always welcomed.â