We met through Sydney share houses in the early 80s when I was in my mid-20s and Tanner, a clever and sweet country boy, was a couple of years older. I first laid eyes on him as he was reaching into a hot oven; he looked up and his gaze met mine. I thought: âWow, he is gorgeous!â

Typical of that time, there were many complicated relationships between housemates and friends. Tanner was in a long-term relationship and it was three years before our feelings for each other spilled over. At a house party we danced to Cold Chiselâs My Baby over and over; another time, at a dinner party at his place, we shared a furtive kiss at the front door as I left.

Over the next few months, we pretended to be just friends in front of others. It was tiresome, confusing and wrong. I told him he needed to make a choice: I would not be âthe other womanâ. To the shock of friends and especially his partner, we began seeing each other publicly and exclusively. Cast out from our social circle and in the heady throes of new love, we began spending nearly every day and night together.

Weâd spend hours talking and writing ridiculous stories and poetry. At sunset weâd sit on the beach and wonder how molluscs knew when the moon and tides were changing. These conversations made my heart sing but Tanner was not one for sharing his feelings. Besides, Tanner, who had been working as a hang-gliding instructor since finishing a PhD in bioscience, was desperate to start his career in scientific research. He was scouring the globe for jobs, and if one came knocking he could leave Sydney at a momentâs notice.

Throughout this hedonistic interlude, I was living in a share house in Clovelly full of alternative, free-spirited types, and swimming every day. I had quit work as an economist to recover from a serious brain injury from a few years earlier.

The brain event had left me with weakness and spasticity on my left side. It also led to a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. After visiting my neurologist with me, Tanner said he thought the MS was not a problem. But I thought it was â life would get messy, I would be a burden and he wouldnât get to live his best life.

So despite my intense feelings, I didnât dare talk with Tanner about our future.

After six months together, he was offered a position at the University of Queensland and left almost immediately. His tiny car was packed to capacity, the hang-glider riding precariously on the roof, as we said goodbye and mumbled vague plans about how Iâd follow him to Brisbane.

Alone in Sydney, I contemplated moving to Brisbane. I was worried about leaving my family and friends, and of course, the ocean. If I was going to make the jump, he needed to know how I felt.

So I wrote a long letter. As I wrote, it dawned on me that what I really wanted was marriage: an old-fashioned, no-holds-barred commitment to permanence and love made in front of friends and family. Fearing I might have misread his feelings and still scared about my health, I came to the big question hesitantly: could I suggest, if I could be so bold, that maybe we could get married?

A couple of days later, I came home to find a letter from Tanner on the hall table. From the postmark, I could tell he had written it before receiving mine: our letters had crossed paths in transit. The door to our lounge room was closed, and inside were a dozen followers of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (or Orange People as they were known then). Bhagwan had just announced that, in light of the growing Aids epidemic, his disciples should forgo their newfound sexual freedom and adopt conservative sexual practices. From my spot in the hallway, I could hear the group were not happy about this.

I opened the letter, and while Tannerâs words were as hesitant and coy as mine, he said he too was in love and proposing marriage.

Overwhelmed with joy I burst into the living room. Holding his letter high, I screeched: âIâm getting married!â The room turned to silence, and then a collective groan, followed by âWhy?â and âAre you crazy?â

But my joyful, gay Orange housemate appeared beside me and screeched back: âOh please can I make the cake?!â

Tanner and I married three weeks later in the church in Bondi where I had been baptised, and it was the best farewell to Sydney ever.

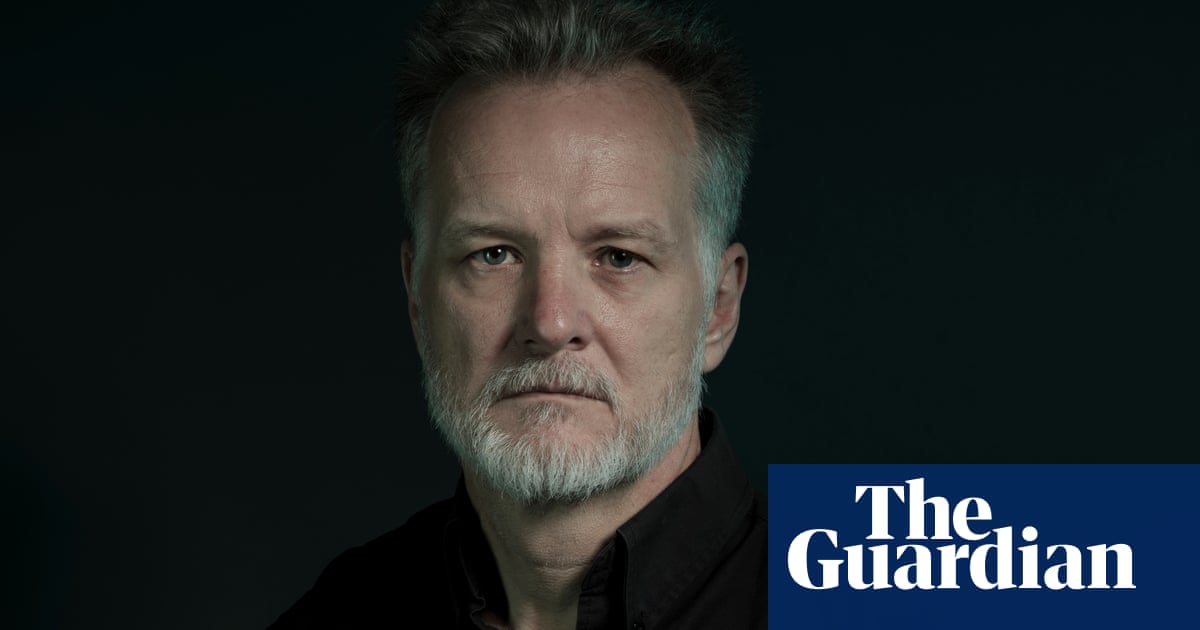

Now, after 40 years of marriage, Tanner still makes my heart sing when I look at his face (especially if heâs getting something out of the oven). We are lucky to have two terrific adult children. My health has been terrible at times and my recoveries remarkable.

The intensity of our early days has been replaced by a calm, knowing we are together no matter what.

Share your experience

Do you have a romantic realisation you’d like to share? From quiet domestic scenes to dramatic revelations, Guardian Australia wants to hear about the moment you knew you were in love.