âThe sea does not belong to despots,â Jules Verne wrote in 1869 in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. âUpon its surface men can still exercise unjust laws, fight, tear one another to pieces, and be carried away with terrestrial horrors. But at 30 feet below its level, their reign ceases, their influence is quenched, and their power disappears.â

Now, more than 150 years later, geopolitics experts are warning that Verneâs final sentiment, expressed as it was through the character of Captain Nemo, was wrong. From seabeds and sea caves to sea canyons, underwater ridges, seamounts, sea knolls and reefs, academics say countries around the world are using the politics of nationalism to permanently stamp their mark on the topography of the ocean.

Klaus Dodds, professor of geopolitics at Royal Holloway, University of London, says that countries today are engaged in a âscramble for the oceansâ. âThereâs more and more ocean grabbing going on in the world, because countries have been given legal permission to do that.â

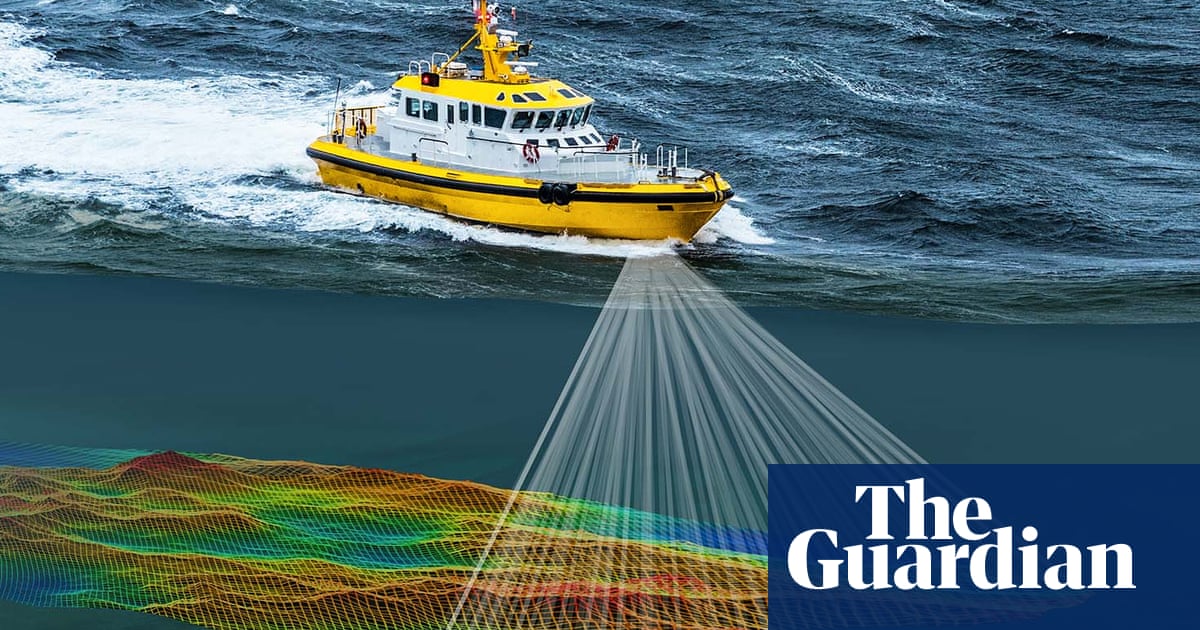

Dr Sergei Basik, a geographer at Conestoga College in Ontario, Canada, says a relatively recent process of 3D mapping the ocean floor has allowed nations to assert their sovereignty over newfound undersea features, known as âbathyonymsâ.

Just as in 1492, when it was a new map of the ocean that inspired and emboldened Christopher Columbus to set sail across the world to find a new trade route to Asia, leading to the colonisation of America, the once murky abyss of the ocean has now resolved into clearly defined topographical features on a 3D map. All of these require a name â and nation states hungry for valuable natural resources and national territory are staking symbolic claims on their âdiscoveriesâ.

âWhen we give a name to an object, we claim it. And we claim not only the surface. We claim the territory and all of its resources,â says Basik. âFrom an economic perspective nations are thinking about the potential [of the features]: how can we use this?â

Basik, who first outlined his thesis in the geography journal Area, fears that countries will one day mine these features for minerals or other economic assets whose power or value is not yet known. âThe first step is the symbolic claim, and after that, weâre talking about commodification of the ocean and resources in the ocean.â

Countries must petition the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), an intergovernmental body based in Monaco with 100 member states, for the right to name the features in internationally recognised nautical charts and documents.

During the 20th century, just 17 names for bathyonyms were proposed on average each year, Basikâs research shows. But since 2000, countries have proposed 95 names on average a year â and recently this trend has strengthened, with more than 1,000 names put forward since 2016.

Basikâs research reveals that Japan is the most zealous proposer of names for seabed objects in the world: it is responsible for naming 615 bathyonyms, followed by the US (560), France (346), Russia (313), New Zealand (308) and China (261).

Dodds says that, in part, this rush to name areas of the seabed has been stimulated by coastal states trying to extend their sovereign rights, which really revolve around potential mineral resources in the sea. âThereâs been a lot of enthusiasm for mapping, surveying and carrying out geological investigations.â

Some countries are seeking to demonstrate that a nearby seabed is part of their continental shelf and therefore belongs to them. This then enables that country â under the rules and procedures of international sea laws â to potentially extend its underwater sovereignty by as much as 350 nautical miles from its coastline, Dodds says. âThese are really huge areas weâre talking about.â

Naming a feature reinforces the point about exclusive ownership. âItâs saying: this is my space.â You name to begin the process of developing a more refined sense of ownership and sovereign authority, he says. For this reason, âthe politics of naming is always tied to expressions of national identityâ.

For example, the Alamang Reefs in the Makassar Strait were discovered by the Indonesian navy in 2022 and named by Indonesia after a traditional Indonesian sword. Similarly, the OâHiggins Guyot and Seamount, which were discovered in the south Pacific by a Chilean vessel, were named by Chile after the 19th-century Chilean independence leader Bernardo OâHiggins Riquelme last year.

Countries do not always restrict themselves to proposing names for geographical features near their own coastlines. âA lot of this attention around naming is now being increasingly developed to ever remoter parts of the seabed,â says Dodds.

For example, Bulgaria, which has a very modest presence in the Antarctic, has been one of the most enthusiastic exponents of Antarctic place naming. âThis is probably a bit counterintuitive, because there are other countries that have done far more in Antarctica and have actually named far fewer features,â says Dodds. âBut Bulgaria has conducted research in the Antarctic. And the whole point about Antarctica and the oceans, at that sort of depth, is that no country is close.â

He adds: âWhatâs happening is weâve got an international legal system that is encouraging mapping and surveying and claiming. And one of the things that historically has driven a lot of this work is an interest in mining the deep seabed.â

For Basik too, the naming â and claiming â of ocean features is not merely a territorial issue. âThis is not only about possible geopolitical conflicts and potential wars,â he says. âThis is about the future and future development. This is about the potential for using the oceans in an absolutely unacceptable manner from an environmental point of view.â